SVCReady: A New Loader Gets Ready

Since the end of April 2022, we have observed new malicious spam campaigns spreading a previously unknown malware family called SVCReady. The malware is notable for the unusual way it is delivered to target PCs – using shellcode hidden in the properties of Microsoft Office documents – and because it is likely in an early stage of development, given that its authors updated the malware several times in May. In this report, we share a closer look at the infection chain of the new SVCReady campaigns, the malware’s features, its changes over time, and possible links with TA551.

Figure 1 – SVCReady sample isolated by HP Wolf Security in April 2022.

Infection Chain

Based on HP Wolf Security telemetry, the first sighting of this new campaign was on 22 April 2022. The attackers sent Microsoft Word document (.doc) attachments to targets via email. As in many other malware campaigns, the documents contain Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) AutoOpen macros that are used to execute malicious code. But unlike other Office malware, the document does not use PowerShell or MSHTA to download further payloads from the web. Instead, the VBA macro runs shellcode stored in the properties of the document, which then drops and runs SVCReady malware.

Figure 2 – Document properties containing shellcode, namely a series of nop instructions as represented by 0x90 values.

Figure 2 – Document properties containing shellcode, namely a series of nop instructions as represented by 0x90 values.

VBA Macro and Shellcode

First, two Windows API functions are defined in the VBA code: SetTimer and VirtualProtect.

![]() Figure 3 – Windows API function definitions.

Figure 3 – Windows API function definitions.

Next the shellcode, which is located in the document properties, is loaded into a variable. Different shellcode is loaded depending on if the architecture of the system is 32 bit or 64 bit.

Figure 4 – Loading shellcode into a variable.

Figure 4 – Loading shellcode into a variable.

The shellcode, now in a variable, is then stored in memory so that it can be assigned executable access rights by calling VirtualProtect. After giving executable access rights to the shellcode, SetTimer is called. The SetTimer API can be passed a callback function as an argument, which is simply a pointer in memory. In this case, the attackers pass the address of the shellcode, thus executing it.

Figure 5 – Change of shellcode protection and execution.

At this point, the execution of the VBA macros ends, and the shellcode takes over the next steps of the infection. First, a dynamic link library (DLL) is dropped into the %TEMP% directory. Next, the shellcode copies rundll32.exe from the Window system directory into the %TEMP% directory. At this point, rundll32.exe is renamed, presumably to evade detection. A detection opportunity here is to alert on the execution of Windows owned binaries outside their standard directories.

Once both files are in the %TEMP% directory, the renamed copy of rundll32.exe is run with the DLL and a function name as arguments. This execution launches SVCReady.

Figure 6 – Rundll32.exe executing the malware.

This infection chain relies on shellcode stored in an Office document, a technique not often seen in malware campaigns. However, we have seen one other campaign that used this technique in mid-April to distribute Ursnif.

The Downloader

The DLL started via rundll32.exe acts as a downloader, with additional functionalities for collecting information about the infected system and communicating with a command and control (C2) server. As soon as the downloader runs, it reports to the C2 server and immediately starts gathering information.

Figure 7 – C2 traffic of downloader, showing a status update (“Starting: success”).

Information Gathering

The malware collects system information including the username, computer name, time zone and whether the computer is joined to a domain. It is also queries the Registry, specifically the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\HARDWARE\DESCRIPTION\System key, for the details about the computer’s manufacturer, BIOS and firmware. Additionally, it collects lists of running processes and installed software. The malware gathers this information through Windows API calls rather than Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) queries. All the information is formatted as JSON and sent to the C2 server through an HTTP POST request.

Figure 8 – Sending system information to the C2 server.

Command and Control

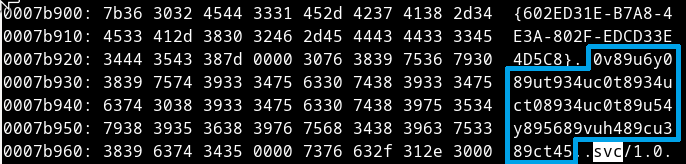

Communication with the C2 server occurs via HTTP, but the data itself is encrypted using the RC4 cipher. Interestingly, RC4 encryption was not implemented in the first malware samples we analyzed at the end of April 2022. This suggests that the C2 encryption was only added during May and that the malware is being actively developed. After unpacking the sample, the RC4 key can be extracted from memory. The attackers change the RC4 key for each campaign.

Figure 9 – The RC4 key used to encrypt the malware’s network communication, shown in memory.

The RC4 key in Figure 9 corresponds to the campaign from 30 May:

- RC4 key – 0v89u6y089ut934uc0t8934uct08934uc0t89u54y895689vuh489cu389ct45

- SVCReady DLL – 16851d915aaddf29fa2069b79d50fe3a81ecaafd28cde5b77cb531fe5a4e6742

Persistence

After exfiltrating information about the infected PC, the malware tries to achieve persistence on the system. The malware’s authors probably intended to copy the malware DLL to the Roaming directory, giving it a unique name based on a freshly generated UUID. But it seems they failed to implement this correctly because rundll32.exe is copied to the Roaming directory instead of the SVCReady DLL. The malware creates a scheduled task called RecoveryExTask that runs the file copied to Roaming with rundll32.exe and a function name when the system starts.

Figure 10 – Definition of the scheduled task.

Figure 10 – Definition of the scheduled task.

But because of the error, rundll32.exe is executed with rundll32.exe, meaning the malware does not start after the system is rebooted.

At this point, the malware creates a new registry key that may be useful for building a signature to detect the malware: HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Classes\CLSID\{E6D34FFC-AD32-4d6a-934C-D387FA873A19}

Figure 11 – Registry key created by the malware.

After completing a task, the malware sends a status message to the C2 server. These status messages are always in JSON format. For example, the status message after creating the scheduled task looks like this:

Figure 12 – JSON status.

More Information Gathering

Once the persistence phase is completed, another information gathering phase follows. This time, the SVCReady takes a screenshot and sends it to the C2 server.

Figure 13 – Sending screenshot to C2.

The malware then runs the systeminfo.exe process. The malware extracts the osinfo section from it and sends it to the C2 server. The information collected is identical to that gathered in the earlier information gathering phase. It is possible that the malware makes this redundant query in case the first queries via Windows API and registry key fail or perhaps the developer was experimenting with different methods of gathering information.

An example output looks like this:

Virtual Machine Detection

Finally, the malware makes two WMI queries that are used to determine whether its runtime environment is virtualized or not:

Select AccessState from Win32_USBControllerDevice

select * from CIM_ComputerSystem

This stage is called checkvm.

Figure 15 – Checking USB controllers to see if it is running inside a virtual machine (VM).

The result of this evaluation is then communicated back to the C2, ending the initial phase of the malware. For example, if a VM is detected:

{“method”:”log”,params”:{“logs”:[“USB Status 2 VM DETECTED “],”stage”:”usbstatus-ban”}}

The malware then enters a sleep stage for 30 minutes.

Figure 16 – Malware going to sleep.

Beaconing activity

SVCReady beacons to its C2 server every five minutes. The beacon only contains the status of the malware. Once the six consecutive sleep instructions have elapsed, the malware validates the last domains received via an HTTP request and then asks for new tasks. The API nodes of the malware gate are structured as follows:

| Purpose | API Node |

| Validate domain | /xl/gate/check |

| Share information | /xl/gate |

| Request tasks | /xl/gate/task |

Figure 17 – C2 response to task request.

The response can include a list of domains and a command for the malware, for example:

{“domains”:[“galmerts[.]art”,”kikipi[.]art”,”kokoroklo[.]su”],”command”:”nop”}

Other functionalities of the malware are:

- Download a file to the infected client

- Take a screenshot

- Run a shell command

- Check if it is running in a virtual machine

- Collect system information (a short and a “normal” version)

- Check the USB status, i.e. the number of devices plugged-in

- Establish persistence through a scheduled task

- Run a file

- Run a file using RunPeNative in memory

Follow-up Malware

In the campaign on 26 April, RedLine Stealer was delivered as a follow-up payload after the initial infection with SVCReady. At that time the C2 communication format was not encrypted. It may be that this campaign was a test by SVCReady’s operators. At the time of writing, we have not yet received any further malware payloads since then. Below are the indicators of compromise (IOCs) for the malware campaign on 26 April:

Word documents:

- fa5747e42c4574f854cd0083b05064466e75d243da93008b9f0dcac5cf31f208

- e09c98b677264fc0de36a9fd99a2711455fe79699ca958938dd12b5bd2c66bad

- c0795d7a7f2c5fdb7615ee5826e8453bef832f36282d6229ec07caf49842f4bc

DLL:

- d3e69a33913507c80742a2d7a59c889efe7aa8f52beef8d172764e049e03ead5

C2 domain:

- muelgadr[.]top

Download URL:

- hxxp://wikidreamers[.]com/exe/install.exe

Payload:

- RedLine Stealer – 6e1137447376815e733c74ab67f202be0d7c769837a0aaac044a9b2696a8fa89

File name and document similarities to TA551

We identified similarities between the file names of the documents used to deliver SVCReady and those used in TA551 campaigns (Figure 18). TA551 activity was last seen at the end of January 2022.

Figure 18 – List of past TA551 threats.

We also found similarities between the lure images used in SVCReady and TA551 campaigns.

Figure 19 – Malicious document containing a social engineering image, April 2022 campaign.

We maintain a database of about 20,000 images extracted from malicious documents, which we use to find visually similar images using perceptual hash algorithms. Figure 20 shows the image extracted from a document that drops SVCReady.

Figure 20 – Extracted image from SVCReady document.

Searching our database revealed three documents used to deliver Ursnif that contained the same image, all from May 2021:

- 2021-05-10: e6afaabd1e4a2c7adeedca6ee0ed095271a53a293162e3cf7ed52d570279258e

- 2021-05-12: 02e62eeb73ac0c0fa55cc203fbee23420a848cf991106eca3f75e8863a0cb4e5

- 2021-05-21: f21289980710dcbb525d70a2be6aa1dc3118150386c0b2196cc5f23e637b87f5

A closer analysis of these documents found that information was also stored in the document properties that was subsequently used by malicious macros. However, the VBA code is significantly different and used MSHTA to download and run the follow-up malware from the web. The malware was downloaded from the following URLs:

- hxxp://192.186.183[.]130/ts/909t5HXsDn4QMY6OB0I8tfpOT0N4FPGKuw~~/40PRbE-lUJTVQYhwM4WoZD6MyfeLT3GeSA~~/

- hxxp://144.168.197[.]36/ts/KS8qyPL1yA-fh8c8BXwFfnOGiWotKKIvqQ~~/t6q4Lknm9T-M1FiPi5sCy2xtzZ27J7KabQ~~/

Ursnif payload hashes:

- 2848bfc05bcfaa5704ff4c44ab86b23c69aa386a39ad4bb393f3287bd884f8cc

- 18d7206e9fa38d5844d3b0ec46576ace8a36091e77477f86a9a43724aa6a2309

Further, our search found two more images that weren’t identical, but still very similar.

Figure 21 – Similar document images from 2019 and 2020.

The difference with this image is that the text is part of the image, whereas in the other campaign, the text and the background were separate element in the document. Notably, the text is identical, including grammatical errors. These two documents were observed in 2019 and 2020 in campaigns that distributed Ursnif and IcedID respectively:

- 2019-02-04: 3dab8a906b30e1371b9aab1895cd5aef75294b747b7291d5c308bb19fbc5db10

- 2020-03-16: e47945f9cc50bb911242f9a69fc4177ed3dcc8e04dbfec0a1d36ff8699541ab5

Both campaigns can be traced back to TA551 based on the domains used to host the malware:

- gou20lclair[.]band

- glquaoy[.]com

Comparing the images used in malware documents provides no certainty that the same threat actor is behind them, since it is possible that we are seeing the artifacts left by two different attackers who are using the same tools. However, our findings show that similar templates and potentially document builders are being used by the actors behind the TA551 and SVCReady campaigns.

Naming the Campaigns

The malware family analyzed in this report corresponds to IDS rules published by Proofpoint, which names it SVCReady. To avoid confusion, we are tracking the malware by the same name.

Conclusion

Since the end of April 2022, we have been seeing new malicious spam campaigns spreading a previously unknown malware family, called SVCReady. Notably, the malware is dropped by shellcode that is stored in the properties of a Word document. SVCReady is under active development. We have tracked several changes since the first campaign in April 2022. The malware also has bugs, notably in its persistence feature and duplication in the reconnaissance data it collects. This, as well as the low frequency and volume of the campaigns, suggests that the malware is in the early stages of development.

Indicators of Compromise

Documents

501D971E548139153C64037D07B4E3FEA2C1735A37774531C88CFA95BA660EC3

99DF2CC2535C82B84BA23384DF290D7506242532123D8414C1CFC61967072C28

C6C080A63DD038D11CD6E724D2DE31108CABE7B6E38F674FE8189696886582AF

D270E1CA349DAA668E0807BE65ECA75CC739008A39E283F922A8728C22663417

6C9FD23D88239D819E0B494E589B665C4E7921ED9B9DD0BBD1610D71230BCF81

F47514C680135C7D4285F2284D5621245463F55A901C38F171DCE445695AC533

9F7124303F1C957F7E02F275F3501CBAA6E0645A6D78B50617A97761DC611CFF

4C1DD6A893F86A150E003118148C655044D06E8300678CF6BF3CC3107B91B66C

FCB325D21D1100269731553015D6D0F85143DAE2BFA6CBAF49AC6DA29F1F732E

939863285773B17623F0F027FAAE8B994BF5FC1AFB182C63A026431C71CD3885

65A650DD353EA767EF68CF4627436977E6D55102D699B2E8B8DE491DA5C0A5EB

134D0B10BAC1404FA1DA83C96C08E0882500819DAAD5F49E9E83C92F2A624B3E

F2FADD7A8B88DA62228DAB8981638B5C9F5512A57A0441B57C2B3A29B0A96012

0D55564A2BED4FF06BC8B1DAAB98E2032C39536DAA31878E16FED29BC987A4D1

A8EED171FDCB2A872865620FC2234E0B07201D927ABCB65344846F6D4A7B75F5

C24266CC16D65F0B8D72BB7DF80A6B2FFE343429A764AFB9FB0A9C20D53AB9AF

50FBE350CC660361B919F5E464DA6D6170F35EF497327AE5DEFC7805E76D5568

C362D9EEFAFB44D4116B4DFABD5945E974C8A010221705E021490EFBF34BC3A3

68617985E8AB455316C18172723FBD2748DE58008714C4CB3F7C6F19D326F135

65E551F7093299A9A20EAF536197C19ABBDD51B95B9570EDAC4950D7C951AD92

D8AEC5539973927EB07A23BA4DE3780D28C2DD2D6DBBC697562A44B30CD3B03F

CA61DE1E2442C16C280EB7264D6B7F79EC92CDC10D1C202EFB028DA5F242F83A

74652EAE27C9F5A5C397EACC76DAF768B3E601F106E8539C7D855712AB185E40

0224B906741F248D8BCEDAEF423B58FFB1B4577EC06711293F7065B12AE71788

FDABB1F5B7691F03B2D89FEB8B0D4E3FD036F9B4E718269CAD8741C7E4D14072

FD799D99F7E84436F8AF16D94EE7B2F1D08CA3CEE746E1CF9B36E2139D676E4C

4A2E76B57DE10C687716A1D7A295910CC5C0D04F5D10D4F4C53AE1BDE45A251C

9122092980BC0ED9C9B008C5456CC18656C41798585B8819F1D6F2620CAC3CF3

391D134B792FB660426F183755AD00DBD737F521CFF1F9A12D402CD714D34645

B67120F25963D36560CBB86B35E864F608536ABEF7C3377F46997D65BAD13CAA

5170461322CB1A79ABB84FEED75B7F871B6F1594562E7724C45D7BB98F97C86B

4B8627B5896A0656E801A95B16068F84660F1460A247E712651E0945EB4309CB

95E328A549247F900DA5747F7E2057DEF121D2EDA82CFD7E926A6955C797D317

AFA40C3157F2704ABA4838A7308B53A4853176AF86982CE2999AA4DF3AC7BB9C

00FD57B32A3DF737C274D2184663DE4EDC22A4E003419C1B10B262E66995EE23

5B7FBEC223DEB714DC7A4037348936A27D86B061CB2120213D5A69849CC9B588

FA6F5695AC2530B486FDD6FE8096AAAF65081BC092AB874545628C61E1403919

C86A477579188305132DAB40700D06FFF9E26B5CE627233FB9D20DA1DFC74B47

748352146AB86EA1A32DFED0B0D5FAC0EFC52728BCCD79476B74FB73517EFB21

DLLs

08e427c92010a8a282c894cf5a77a874e09c08e283a66f1905c131871cc4d273

16851d915aaddf29fa2069b79d50fe3a81ecaafd28cde5b77cb531fe5a4e6742

1d3217d7818e05db29f7c4437d41ea20f75978f67bc2b4419225542b190432fb

235720bec0797367013cbdc1fe9bbdde1c5d325235920a1a3e9499485fb72dba

39c955c9e906075c11948edd79ffc6d6fcc5b5e3ac336231f52c3b03e718371e

5e932751c4dea799d69e1b4f02291dc6b06200dd4562b7ae1b6ac96693165cea

d3e69a33913507c80742a2d7a59c889efe7aa8f52beef8d172764e049e03ead5

f690f484c1883571a8bbf19313025a1264d3e10f570380f7aca3cc92135e1d2e

Domains

muelgadr[.]top

wikidreamers[.]com

galmerts[.]art

marualosa[.]top

kikipi[.]art

kokoroklo[.]su